Ocean Acidification, also known as the “Other Carbon Problem,” is a problem plaguing the oceans around the world due to the rising CO2 emissions on our planet. Since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, the ocean’s acidity has dropped by 0.1 pH units, which is approximately a 30% increase in acidity, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the 2007 the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) report on climate change. Worse yet, they predict that by the end of the century, the surface waters of the oceans could be nearly 150% more acidic. With this steadily alarming decrease in pH, certain areas of the ocean, especially Antarctica, will become corrosive by the end of the century.

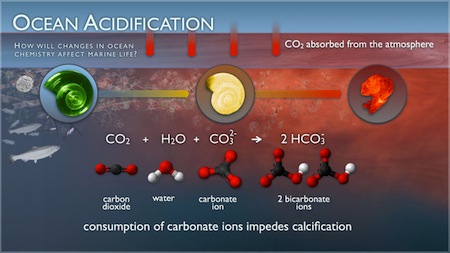

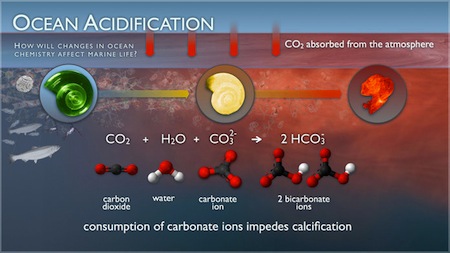

Ocean acidification will affect shelled organisms, says the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), an environmental group. With the heightened acidity of the water, the amount of carbonate—the primary mineral to form shells and skeletons in many varieties of shellfish and corals—will be greatly reduced. Similar to osteoporosis in humans, if the growth of the shells is slowed down, it makes them significantly weaker, according to Kathleen McAuliffe, a science and health writer for Discover.

The three main marine organisms that rely on the carbonate in the water are pteropods, shellfish, and corals Pteropods are tiny organisms that act as a main food for larger species, such as whales and salmon. In 2008, the NOAA estimated the worth of the shellfish industry at approximately $100 million per year. And coral are very important to the entire ecosystem of the ocean because they provide a habitat and protection for many species. Coral produces calcium carbonate shells, but when the pH of the water is reduced, they have a hard time producing their skeletons. Studies by NOAA have also shown that decreased pH can also negatively affect the reproduction of the species.

| Related story: Can Teens Solve the Global Climate Change Problem |

2100, he was able to show that they do not develop the hearing abilities needed to survive and avoid predators on the reef.

According to NOAA, the oceans absorb 25% of the carbon dioxide from the air. However, carbon dioxide can spend a long time in the atmosphere and the ocean’s water circulates slowly. The CO2 from the air dissolves in the water producing carbonic acid ( (H2CO3). This chemical, which can become harmful in large quantities, can become destructive toward the animals when too much of it is introduced into the ocean and, as a result, change the water’s pH. The world’s oceans currently have a pH between 7.8 to 8.5, with 7 being neutral. The IPCC estimates that the pH of the ocean will drop another 0.3 to 0.4 units by the year 2100.

As Britain’s Royal Society noted in 2005, it will take “tens of thousands of years for the ocean chemistry to return to a condition similar to that occurring at pre-industrial times.”

“The oceans do a lot for us. They provide us with food, produce oxygen (phytoplankton), etc. As the oceans become more and more acidic, what we risk is losing some species,” said Raphaelle Descoteaux, a Marine Biology Master’s student at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, in an email correspondence. She is currently studying the effects of ocean acidification on crab larvae in Alaska. “Everything is connected in the oceans, so once you start playing with one component, there can be a chain reaction on other components as well.”

The first buoy to monitor ocean acidification was launched in June 2007 in the Gulf of Alaska. This buoy is equipped with sensors to measure climate and the exchange of carbon dioxide exchange between the air and the ocean. Researchers hope that data gained from this buoy will allow for a better understanding of ocean acidification and how it can be reversed.

Josi Taylor, a Postdoctoral scientist at Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute who is currently studying ocean acidification, said in an email correspondence: “The only thing that can be done to slow ocean acidification is to reduce how much CO2 enters the atmosphere. There is nothing we can do naturally to reverse the process; just slow it down. Things as simple as shutting off the lights when you leave a room, or using high efficiency appliances, can make a big difference when more people do them.” Maggie Rabenberg

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License

There has to be a way to raise the pH levels, we just have to find it

There has to be a way to raise the pH levels, we just hsve to find it :smile

thank you so much:good